(This reading is part of Activity 9: The feminist challenge: how feminism expands ideas of freedom.)

By Frances Rogan and Shelley Budgeon, 9 August 20181

The slogan, ‘the personal is political’, has its origins in a paper of the same title authored by Carol Hanisch. It was published in 1970 as part of a collection of essays called Notes from the Second Year: Women’s Liberation. Hanisch was motivated to write the paper in defence of Women’s Liberation Movement groups who were emerging out of existing radical movements such as the Civil Rights movement, the Anti-Vietnam War movement, and Old and New Left groups. Because these movements tended to be male-dominated, the specificity of women’s oppression was not deemed relevant to the political struggles these groups defined as their focus.

As women from these movements began to organise and name their oppression, Hanisch recounts how the women within the Women’s Liberation Movement were ‘belittled’ to no end for trying to bring their so-called ‘personal problems’ into the public arena, especially ‘all those body issues like sex, appearance, and abortion’. Their concerns were regarded as isolated ‘personal’ issues best addressed through individual initiative, and as such, not the proper focus for radical political organisations associated with existing leftist movements. The practice of consciousness raising (women gathering together to discuss their own oppression) was condemned as mere ‘personal therapy’ or ‘navel gazing’.

A number of linked threads, which run through Hanisch’s essay, warrant unpacking as they form the basis for a fundamental feminist theory of the constitution of gender relations, which continues to resonate with contemporary critiques of gender relations. These threads broadly fall under four interrelated categories: (i) power (ii) the separation between the private and public realm (iii) political action (iv) and everyday experiences.

Second-wave Fundamentals

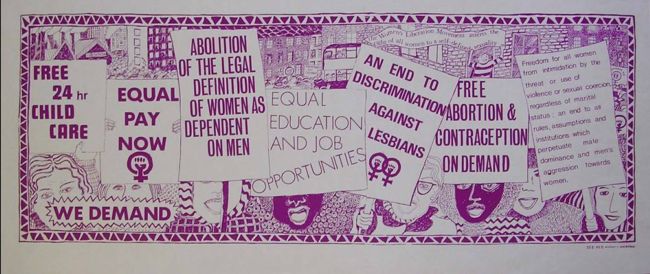

Feminism, like liberal political theory, endorsed the tenet which holds individuals are ‘free and equal beings who are freed from the ascribed, hierarchical bonds of traditional society’. Demands by second-wave feminism for the full extension of liberal principles and rights to women represented a significant move towards the completion of the liberal project. The failure of liberalism to deliver on this promise, therefore, was a central plank in the politics of the Women’s Liberation Movement. Without an adequate theory of power, grasping the limits of liberal theory was not possible. Hence, understanding that women’s exclusion was the product of the essentially patriarchal constitution of liberal thought was a critical element in developing feminist critique.

Carole Pateman’s 1983 classic essay begins with the assertion that ‘the separation between the private and the public is central to almost two centuries of feminist writing and political struggle; it is, ultimately what the feminist movement is about’. A theory of patriarchal power was brought to bear in her critique of liberal political theory, and in so doing, she drew together a set of theoretical principles that explained the oppression of women as the product of historically specific structures of domination and subordination.

*Liberalism is an individualist, egalitarian, conventionalist doctrine; patriarchalism claims the hierarchal relations of subordination necessarily flow from the natural characteristics of men and women. In fact, the two doctrines were successfully reconciled through the answer given by the contract theorists in the seventeenth century to the subversive question of who counted as free and equal individuals (Pateman 1983, p. 283, emphasis added).*

The justification for not extending rights to women relied fundamentally upon the separation of spheres whereby political power in the public sphere was not to be confused with paternal power which governed familial relations in the private sphere. The exercise of male power over women in the private sphere was commonly understood to arise out of nature and as such was fundamentally different from the forms of power which governed the public sphere. Patriarchal power operated to produce gender as a relation founded on ‘natural’ male superiority and not the product of structural social relations. Women (wives) as natural subordinates could not be ‘free and equal’. Thereby, an inherent contradiction in liberal political theory was resolved (Pateman 1983, p. 284).

Second-wave feminism challenged and politicised this assertion of natural difference and the associated conviction that it would be ‘unnatural’ to extend the rights of the free individual and autonomous subjecthood to women.

This analysis of patriarchal power illustrates that gender inequality depends upon denying that particular aspects of everyday life have political importance. By asserting that issues such as sexuality or the body are not ‘merely’ private matters second-wave feminism politicised socio-spatial relations structured by the gendered public/private distinction. In the introduction to the anthology of writings from the WLM, Sisterhood is Powerful, editor Robyn Morgan explains the unique nature of the collection highlighting the way it combines ‘all sorts of articles, poems, graphics and sundry papers’ that reflect a range of experiences defined by women as central to their oppression. The variety of topics covered and the formats of expression employed illustrate that ‘Women’s liberation is the first radical movement to base its politics—and, in fact, create its politics—out of personal experiences. We’ve learned that those experiences are not our private hang-ups’. Second-wave feminism significantly extended critical understanding of how power flows through the micro level interstices of everyday life.

Whatever else feminist politics have done in the last decade, they have broadened the concept of the political. In saying “our politics begins with our feelings”—rather with our exercise of the franchise (vote)—feminists are drawing attention to the fact that the field of what is usually considered political is a created one. Politics, in any and every sense, is about power, and it is as much about the power that men, wittingly or unwittingly, exercise over women as it is about the power that presidents and prime ministers wield over nations.

The insight that laid bare the power relations governing ‘private’ experience led to more nuanced understandings of what types of activities could form part of a broader political movement concerned with the advancement of women’s interests. Practices such as consciousness raising were not, therefore, merely individualistic personal therapy but rather provided the basis for generating identification with a wider collective social experience that arose out of specific social and political forces. As Hanisch argued in 1969 in defence of consciousness raising groups, it is a ‘political action to tell it like it is, to say what I really believe about my life instead of what I’ve always been told to say’ (Hanisch 2006). Practices which seemed to be about women’s everyday lives and experiences were theorised as fundamentally political.

Our politics begin with our feelings …. The political unit in which we can discover, share and explore our feelings is the small group. Raising our collective consciousness is not a process that begins and ends, but is continuous and necessary given the enormous pressure placed on us everywhere to deny our own perceptions (San Francisco Redstockings 1969, pp. 285–86).

This approach to theorising experience was also central to the ‘personal genesis of Black Feminism’ which arose from ‘the seemingly personal experiences of individual Black women’s lives. For women of colour, the act of claiming the specificity of their oppression became foundational to a politics which challenged both the sexism they experienced within their own communities and the racism they experienced within predominantly white feminist communities. Moreover, naming their oppression exposed the ‘false universalism of “women’s experience” ‘(Phipps 2016, p. 305).

Finally, the slogan encouraged the notion that these practices, undertaken in places and spaces not conventionally defined as political, would contribute to the development of new female political feelings (or subjectivity) that would enable women to speak as autonomous political subjects. These included not only those rights conventionally assigned to the individual within traditional liberal political theory, but a set of newly self-defined rights that related to issues such as sexuality and the body.

In order to create an alternative, an oppressed group must once shatter the self-reflecting world which encircles it and, at the same time, project its own image onto history. In order to discover its own identity as distinct from that of the oppressor, it has to become visible to itself… As we begin to know ourselves in a new relation to one another we can start to understand our movement in relation to the outside world. We can begin to use our self-consciousness strategically. We can see what we could not see before (Rowbotham 1973, pp. 27–28).

In summary, by theorising gender as a product of patriarchal power relations, the Women’s Liberation Movement extended the definition of politics to areas of everyday life formerly trivialised and understood as natural, challenged conventional norms that defined political action, and developed a set of strategies that allowed women to discover the political nature of their experiences as the foundation for activism.

- This is an adapted and shortened version of the paper. ^